Having worked on a variety of projects designed to improve the lives of poor, I’ve frequently heard the idea floated that we should always focus on ‘teaching people to fish’. In short, we should aim for sustainable solutions that are designed to reduce the dependency of target beneficiaries, after all:

“If you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day. If you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.”

Completely reasonable advice: after all, why shouldn’t beneficiaries be empowered to provide for themself rather than relying on the generosity of others?

The answer is they shouldn’t: After all, by the time you’re born the scope of opportunities available to you are bounded. Where and when you’re born, your gender and the family you’re born in will all influence the options available to you — regardless of grit.

Teaching people to fish therefore means: identifying those in need; finding a way to improve their lives; and implementing a solution that doesn’t require indefinite external support. Or, using the ‘fishing’ metaphor: finding those that don’t know how to fish, buying them a rod, reel and bait, and teaching them how to use it.

Context is Everything: the water we swim in

The problem is, we often don’t know how to fish as in the words of Tyler Cohen: “Context is that which is scarce.” Context is important, but something we’re rarely aware of. It is the water in which we swim.

Catching the bus to work, we can take the existence of a regular bus schedule for granted. Paying your fare when you reach your stop, you probably don’t consider why it’s even possible to pay for your ride with pieces of metal and paper. And arriving at work, you might not even think about why you didn’t need to pay a bribe to the security guard that after you forgot your security credentials.

If you live in a democracy, with a reasonably effective government and low corruption you’re already ahead. Whether you can find a job, get access to adequate healthcare and attend university: this is the water in which you swim.

Fishing 101

Which is a good way to introduce my first problem with applying the adage: if context matters, but we aren’t aware of it, how can we be sure that it’s our fishing technique that underlies our success?

Little fish, big pond

Take national economic development as a macro example. Using measures such as economic growth and social outcomes like life expectancy and education outcomes, we can get a pretty good idea which countries know how to fish: they’re healthier, wealthier and better educated than those that don’t.

Alas, while there is reasonable agreement on the characteristics of high growth countries – high aggregate investment, high human capital, stable population growth, political stability, functioning markets and a developed financial system – the causal mechanisms behind these characteristics is still contested, as noted by Mankiw:

“…using these regressions to decide how to foster growth is … most likely a hopeless task. Simultaneity, multicollinearity, and limited degrees of freedom are important practical problems for anyone trying to draw inferences from international data. Policymakers who want to promote growth would not go far wrong ignoring most of the vast literature re-porting growth regressions…”

Mankiw (1995), “The growth of nations”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1995 (1): 275-310

Meaning we’re not only unclear about which policies are needed to achieve economic growth, but also pretty poor at implementing pro-growth policies across social, economic and cultural contexts.

Big fish, small pond

So, teaching an entire nation how to fish is hard. Who’d have guessed?!

This is probably a good reason to start small. Rather than teaching a nation how to fish, let’s start by helping a single community, household or even an individual. We can focus on small uncomplicated solutions, monitor their success, repeat what works and drop what doesn’t.

Unfortunately, the world doesn’t always behave, take this example from research by Martin Williams:

“…the Tamil Nadu Integrated Nutrition Programme (TINP), and the Bangladesh Integrated Nutrition Programme (BINP). The TINP project was implemented in the 1990’s and sought to improve child nutrition in rural Tamil Nadu by simultaneously delivering two interventions:

- Supplementary food for pregnant or nursing mothers and their children; and

- nutritional advice to mothers to correct a miss-perception that mothers should reduce rather than increase their food intake during pregnancy…”

The results: A rigorous impact evaluation showed that the project was successful: mothers’ nutritional knowledge improved, mothers and children consumed more food, and children malnutrition and stunting decreased significantly (source).

Martin Williams, External Validity and Policy Adaptation: From Impact Evaluation to Policy Design.

Unfortunately, when the program was trialed in Bangladesh results weren’t nearly as positive. The reason – unlike Tamil Nadu, the fathers (or their mothers) were responsible for making decisions on food allocations and shopping.

Fishing in Tamil Nadu differed just enough from Bangladesh to affect the catch. One seemingly inconsequential difference is all it took for an effective program to be transformed into an ineffective one.

But surely this is just an amusing story that development economists tell each other at cocktail parties (assuming they’re invited) – just an outlier, not the norm?

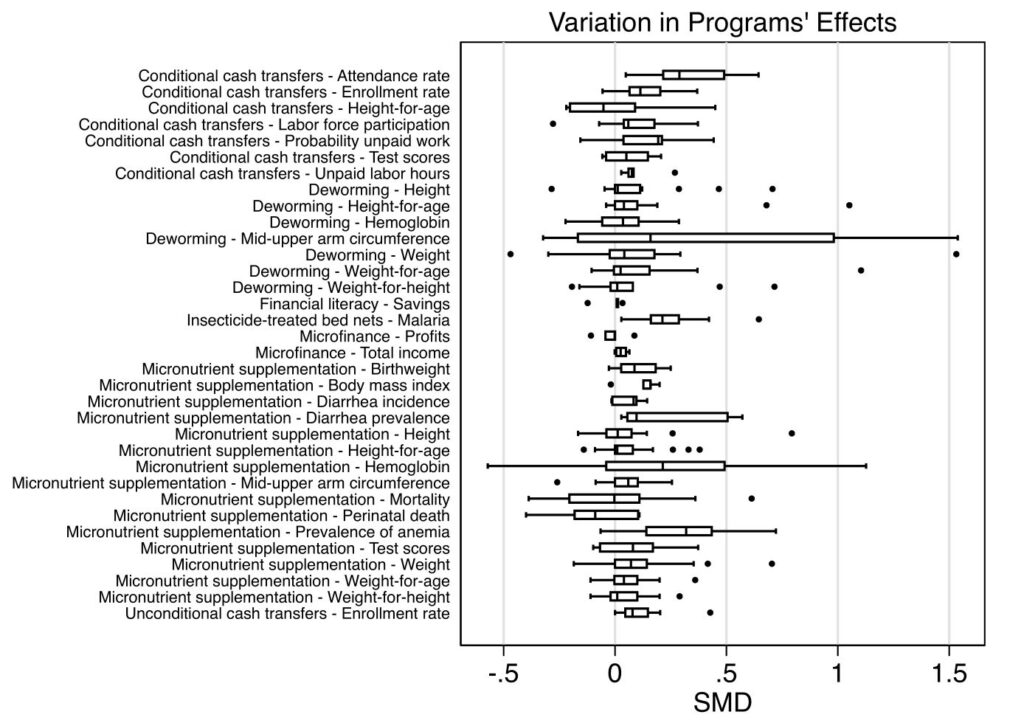

Eva Vivalt research explored this very question by reviewing 635 papers covering 20 different types of intervention to see just how likely it is that we’ll get similar results if we implement the same program somewhere else.

Her results: getting the same results is not very likely. Finding not only that the same program had vastly different outcomes when repeated, but that the outcomes of comparable programs were themselves not necessarily comparable even when conducted in the same country. Meaning that not-for-profits, policymakers and change makers can’t necessarily rely on past success to guarantee a program will be effective in the future i.e. teaching one man to fish doesn’t guarantee you can teach another.

Teaching People How to Fish

So where exactly does this leave us?

Well, as a general rule it’s probably not a good idea to assume something that works here will necessarily work there. Particularly if the success of your approach or program stems from reliable power, effective governance and strong social cohesion. Pretty standard stuff in the world of public policy and international development.

Unfortunately, what this also means is that while teaching others to fish is a laudable goal. We probably don’t know how. Both because, past success is no guarantee of future success (as evidenced by Eva Vivalt’s study). And, being blind to many of the contextual factors that lead to success, we aren’t likely to be as good at fishing as we might think — making us lousy teachers.

Leave a Reply